From "Before Collapse," di Ugo Bardi, Springer 2019 (*)

In military matters, there exists an “anti-Seneca” strategy that consists in disregarding Sun Tzu’s principle of minimum effort, aiming instead at continuing the war all the way to the complete military defeat, or even the annihilation, of the enemy. Such a plan could be based on ideological, political, or religious considerations leading one or both sides to believe that the very existence of the other is a deadly threat that must be removed using force. In ancient times, religious hatred led to the extermination of entire populations, and there is a rather well-known statement that may have been pronounced after the fall of the Albigensian city of Béziers, in Southern France, in 1209. It is said that the Papal legate who was with the attacking Catholic troops was asked what to do with the citizens, which surely included both Catholics and Albigensian heretics. The answer was, "Kill them all; God will know His own."

That war, just like most modern wars, was an “identity war” where the enemy is seen as not just an adversary, but an evil entity to be destroyed. These wars tend to be brutal and carried on all the way to the total extermination of the losing side. In some cases, though, wars may be prolonged simply because they are good business for some people and companies on both sides.

A possible case of this kind of “anti-Seneca” strategy may be found in the campaign that was started in the US in 1914 to provide food for Belgium during the First World War. The campaign is normally described as a great humanitarian success, but in the recent book Prolonging the Agony (2018), the authors, Docherty and Macgregor, suggest that the relief effort was just the facade for the real task of the operation: supplying food to Germany so that the German army could continue fighting until it was completely destroyed. This interpretation appears to be mainly speculation, but we can't ignore that Belgium was occupied by the German army at that time, and so it could be expected that at least part of the food sent there would end up in German hands.

Something more ominous took place during the Second World War. By September 1943, after the surrender of Italy, it must have been clear to everybody on both sides that the Allies had won the war; it was only a question of time for them to finish the job. So, what could have prevented the German government from following the example of Italy and deciding to surrender, maybe ousting Hitler, as the Italian government had done with Mussolini? We do not know whether some members of the German leadership considered this strategy, but it seems clear that the Allies did not encourage them. One month after Italy surrendered, in October 1943, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, signed a document known as the “Moscow Declaration.” Among other things, it stated that:

At the time of granting of any armistice to any government which may be set up in Germany, those German officers and men and members of the Nazi party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in the above atrocities, massacres and executions will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done … and judged on the spot by the peoples whom they have outraged.

… most assuredly the three Allied powers will pursue them to the uttermost ends of the earth and will deliver them to their accusors in order that justice may be done. … <else> they will be punished by joint decision of the government of the Allies.

What was the purpose of broadcasting this document that threatened the extermination of the German leadership, knowing that it would have been read by the Germans, too? The Allies seemed to want to make sure that the German leaders understood that there was no space to negotiate an armistice. The only way out left to the German military was to take the situation into their own hands to get rid of the leaders that the Allied had vowed to punish. That was probably the reason for the assassination attempt carried out against Adolf Hitler on June 20th, 1944. It failed, and we will never know if it would have shortened the war.

Perhaps as a reaction to the coup against Hitler in Germany, a few months later, on September 21, 1944, the Allies publicly diffused a plan for post-war Germany that had been approved at the Quebec Conference by the British and American governments. The plan, known as the “Morgenthau Plan,” was proposed by Henry Morgenthau Jr. secretary of the Treasury of the United States. Among other things, it called for the complete destruction of Germany’s industrial infrastructure and the transformation of Germany into a purely agricultural society at a nearly Medieval technology level. If carried out as stated, the plan would have killed millions of Germans since German agriculture, alone, would have been unable to sustain the German population. The plan was initially approved by the US president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Unlike the Moscow declaration that aimed at punishing German leaders, the Morgenthau plan called for the punishment of the whole German population. Again, the proponents could not have been unaware that their plan was visible to the Germans and that the German government would have used it as a propaganda tool. President Roosevelt's son-in-law, Lt. Colonel John Boettiger, stated that the Morgenthau Plan was "worth thirty divisions to the Germans." The general upheaval against the plan among the US leadership led President Roosevelt to disavow it. But it may have been one of the reasons that led the Germans to fight like cornered rats to the bitter end.

So, what was the idea behind the Morgenthau plan? As you may imagine, the story generated a number of conspiracy theories. One of these theories proposes that the plan was not conceived by Morgenthau himself, but by his assistant secretary, Harry Dexter White. After the war, White was accused of being a Soviet spy by the Venona investigation, a US counterintelligence effort started during WW2 that was the prelude to the well-known “Witch Hunts” carried out by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. According to a later interpretation, White had acted under instructions from Stalin himself, who wanted the Germans to suffer under the Allied occupation so much that they would welcome a Soviet intervention. It goes without saying that this is just speculation, but, since this chapter deals with the evil side of collapse, this story fits very well with it.

There is no evidence that the Morgenthau plan was conceived by evil people gathering in secret in a smoke-filled room. Rather, it has certain logic if examined from the point of view of the people engaged in the war effort against Germany in the 1940s. They had seen Germany rebuilding its army and restarting its war effort to conquer Europe just 20 years after it had been defeated in a way that seemed to be final, in 1918. It is not surprising that they wanted to make sure that it could not happen again. But, according to their experience, it was not sufficient to defeat Germany to obtain that result: no peace treaty, no matter how harsh on the losers, could obtain that. The only way to put to rest the German ambitions of conquest forever was by means of the complete destruction of the German armed forces and the occupation of all of Germany. For this, the German forces had to fight like cornered rats. And it seems reasonable that if you want a rat to fight in that way, you have to corner it first. The Morgenthau plan left no hope for the Germans except in terms of a desperate fight to the last man.

We do not know whether the people who conceived the plan saw it in these terms. The documents we have seem to indicate that there was a strong feeling among the people of the American government during the war about the need to punish Germany and the Germans, as described, for instance, in Beschloss’s book The Conquerors. Whatever the case, fortunately, the Morgenthau plan was never officially adopted, and, in 1947, the US changed its focus from destroying Germany to rebuilding it by means of the Marshall plan.

There have been other cases of wars where there was no attempt to apply the wise strategy proposed by Sun-Tzu, who suggests always leaving the enemy a way to escape. Nowadays, wars seem to be becoming more and more polarized and destructive, just like the political debate. Once a war has started, the only way to conclude it seems to be the complete collapse of the enemy and the extermination of its leaders. The laughter of the US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, at the news of the murder of the leader of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi, in 2011 is a case in point of how brutal these confrontations have become. It is hard to see how the trend in this direction could be reversed until the current international system of interaction among states that created it collapses. At least, it should be clear that the anti-Seneca strategy is an especially inefficient way to win wars.

⸐

(*) This is a lightly edited text from an early version of the book.

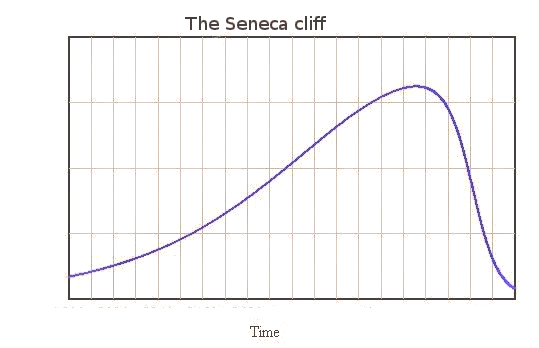

The Seneca Effect: why decline is faster than growth

The Seneca Effect: why decline is faster than growth